On Optimization in Deep Learning

This is an old post which may not fit into modern view. Some recent finding such as lottery ticket theory is not covered in this post.

There are at least exponentially many global minima for a neural net. Since permuating the nodes in one layer does not change the loss. Finding such points is not easy. Before certain techniques such as momentum came out, those nets were considered impossible to learn.

Thanks to the constantly envolving hardwares and libraries, we do not have to worry about training time that much at least for convnets. Empirically, the non-convexity of neural nets seems not to be an issue. In practice, SGD works pretty well in optimizing very large networks even though the problem is proved to be NP-hard. However, researchers never stop studying the loss surface of deep neural nets and searching for better optimization strategies.

This paper has been renewed on ArXiv recently, which leads me to this discussion. Following are what I find interesting.

Why SGD works?

[Choromaska et al, AISTATS’15] (also [Dauphin et al, ICML’15] use tools from Statistical Physics to explain the behavior of stochastic gradient methods when training deep neural networks. This offers a macroscopic explanation of why SGD “works”, and gives a characterization of the network depth. The model is strongly simplified, and convolution is not considered.

Saddle points

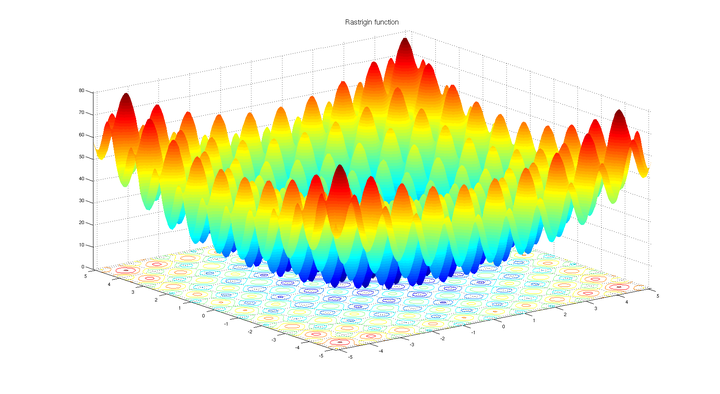

We start from discussing saddle points, the vast majority of critical points on the error surfaces of neural networks.

Here we argue, … that a deeper and more profound difficulty originates from the proliferation of saddle points, not local minima, especially in high dimensional problems of practical interest. Such saddle points are surrounded by high error plateaus that can dramatically slow down learning, and give the illusory impression of the existence of a local minimum.

– Dauphin et al, Identifying and attacking the saddle point problem in high-dimensional non-convex optimization

The authors introduce saddle-free Newton method which requires the estimation of Hessian. They connect the loss function of a deep net to a high-dimensional Gaussian random field. They show that critical points with high training error are exponentially likely to be saddle points with many negative directions, and all local minima are likely to have error that is very close to that of the global minimum. (Described in Entropy-SGD: Biasing Gradient Descent Into Wide Valleys.)

The convergence of gradient descent is affected by the proliferation of saddle points surrounded by high error plateaus — as opposed to multiple local minima.

The time spent by diffusion is inversely proportional to the smallest negative eigenvalue of the Hessian at a saddle point

– Kramer’s law

It is believed that for many problems including learning deep nets, almost all local minimum have very similar function value to the global optimum, and hence finding a local minimum is good enough.

– Rong Ge, Escaping from Saddle Points

As the model grows deeper, local minima have loss closer to global minima. On the other hand, we do not care about global minimum because it often leads to overfitting.

Saddle points exist along the paths between local minima, most objective functions have exponentially many of those. However, first order optimization algorithms may get stuck at saddle points. Strict saddle points can be escaped and global minima can be achieved in polynomial time ( Ge et al., 2015). Stochastic gradient introduces noise and help to push the current point away from saddle points.

Non-convex problems can have ‘‘degenerate saddle points’', whose Hessian is p.s.d. and have 0 eigenvalues. The performance of SGD on these kind of tasks is still not well studied.

To conclude this part, AFAIK, we should care more about escaping from saddle point. And gradient based methods can do a better job than second-order methods in practice.

Spin-glass Hamiltonian

See Charles Martin: Why Does Deep Learning Works? Both papers mentioned above use ideas from statistical physics and spin-glass models.

Statistical physicists refer to $H_x(y)\equiv-\ln p(y|x)$ as the Hamiltonian, quantifying the energy of $y$ given the parameter $x$. And $\mu\equiv -\ln p$ as self-information. We can rewrite Bayes’ formula as:

$$ p(y) = \sigma(-H(y)-\mu) $$

We can see the features yield by a neural net as Hamiltonian and the softmax computes the classification probability.

The long-term behavior of certain neural network models are governed by the statistical mechanism of infinite-range Ising spin-glass Hamiltonians

– LeCun et. al., The Loss Surfaces of Multilayer Networks, 2015

In this paper, he tries to explain the optimization paradigm with spin-glass theory.

Implicit Bias in SGD

- Chaudhari proposed a surrogate loss that explicitly biases SGD dynamics towards flat local minima. The corresponding algorithm relates closely to stochastic gradient Langevin dynamics.

- Another interpretation is that SGD performs Variational Inference (VI).

What does the minima look like?

Take for example the concept of mode connectivity ( Garipov et al, 2018): it seems that the modes found by SGD using different random seeds are not just isolated basins, but they are connected by smooth valleys along which the training and test error are low.

No poor local minima

Research at Google and Stanford confirms that the Deep Learning Energy Landscapes appear to be roughly convex. A bolder hypothesis is that deep networks are spin funnels. And as the net gets larger, the funnel gets sharper. If this is true, our major concern should be to avoid over-training rather than the convexity of the network.

Finally we arrive at the paper itself. Nets are optimized well by local gradient methods and seems not to be affected by local minima. The author claims that every local minimum is a global minimum and “bad” saddle points (degenerated ones) exists for deeper nets. Thm 2.3 gives clear result on linear networks.

The main result Thm 3.2 generalizes Choromanska et al, 2015‘s idea for nonlinear network relies on 4 (seemingly strong) assumptions:

- The dimensionality of the output is smaller than the input.

- The inputs are random and decorrelated.

- A connection in the network is activated or not is random with the same probability of success across the network. (ReLU thresholding happens randomly.)

- The network activations are independent of the input, the weights and each other.

They relax the majority of the asssumptions, which is very promising, but leave a weaker condition A1u-m and A5u-m ( from reddit post).

Recently DeepMind came up with another paper claiming the assumptions are too strong for real data. And devised counter examples with finite datatets for rectified MLPs. For finite sized models/datasets, one does not have a globally good behavior of learning regardless of the model size.

Even though deep learning energy landscapes appear to be roughly convex, or as this post referred to, local minimal free, a deep model has to include more engineering details to aid its convergence. Problems such as covariance shift and overfitting still have to be handled by engineering techniques.

Arriving on flatter minima

large-batch methods tend to converge to sharp minimizers of the training and testing functions – and that sharp minima lead to poorer generalization. In contrast, small-batch methods consistently converge to flat minimizers, and our experiments support a commonly held view that this is due to the inherent noise in the gradient estimation.

– On Large-Batch Training for Deep Learning: Generalization Gap and Sharp Minima

Should 2-nd order methods ever work?

Basiclly no. Because the Hessian vector product require very low variance estimation, which leads to batch size larger than 1000. But some rare cases happen when 2nd order methods with small batch size works.

Gradient Starvation

-

On the Learning Dynamics of Deep Neural Networks

- Some features will dominate the gradient and sheding other equally important features.